Once a beacon of hope for affordable housing enthusiasts, the tiny house movement in New South Wales (NSW) has seen its star dim since its heyday in 2018-2019. The allure of living simply, sustainably, and affordably captivated many Australians, especially as housing prices soared. Yet, despite the promise of tiny houses, their growth in NSW has stagnated. This is not due to a lack of interest, but rather the result of logistical, regulatory, and infrastructural hurdles that have stymied their broader adoption.

The Promise of Tiny Living

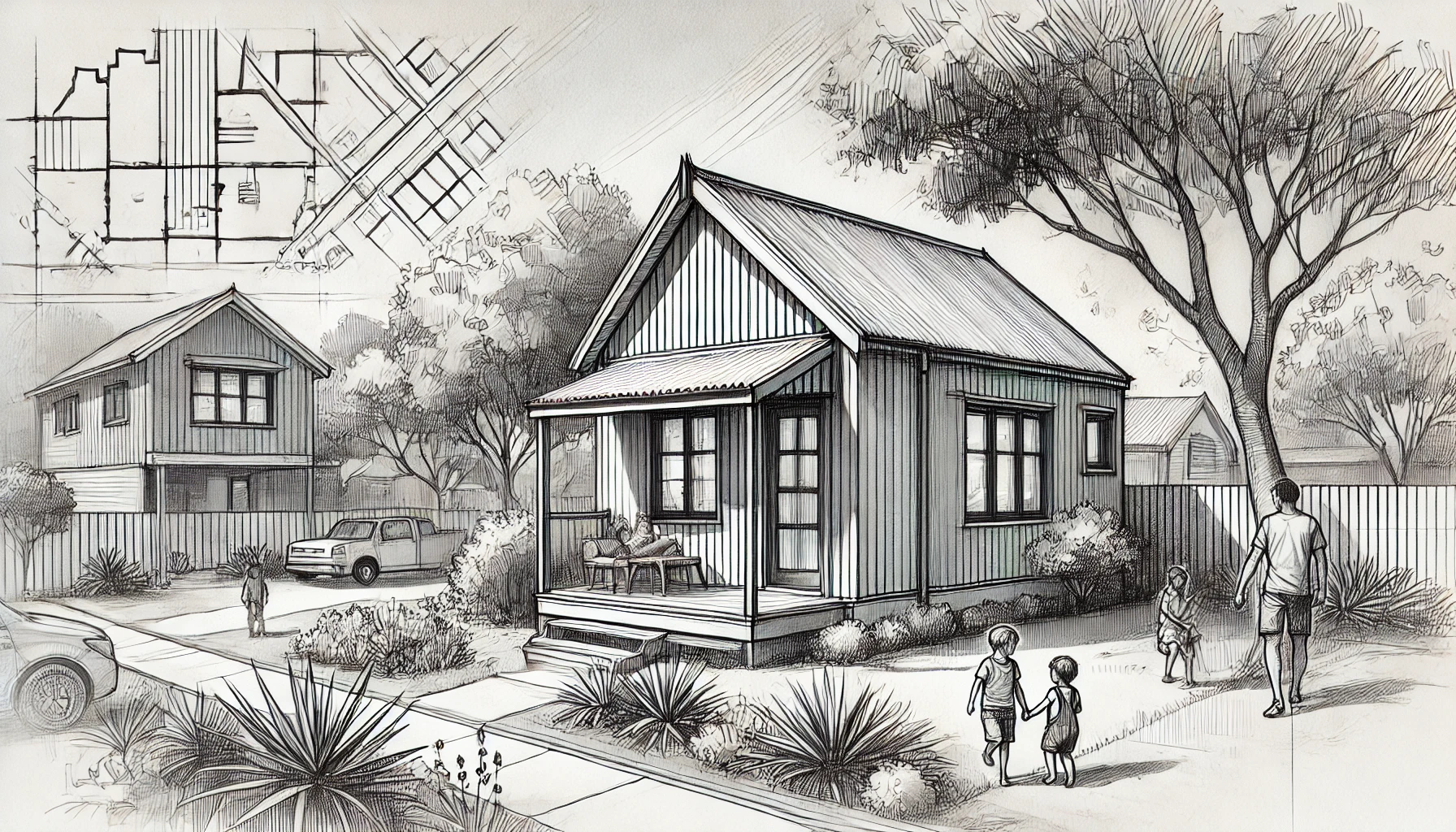

The concept of tiny houses — compact dwellings typically ranging from 15 to 50 square meters — is rooted in minimalism and sustainability. Their smaller footprints make them environmentally friendly and significantly cheaper to build than traditional homes. In Australia, the average cost of a tiny house begins at around $150,000, a fraction of Sydney's median house price of $1.36 million as of late 2024. This affordability makes tiny homes especially appealing to younger generations, retirees looking to downsize, and those priced out of the traditional housing market.

Beyond cost, the tiny house movement promotes a lifestyle of reduced consumerism and closer connections to nature, often achieved by locating homes in rural or semi-rural settings. However, the idyllic vision of tiny house living comes crashing into the realities of zoning laws, land access, and public perception.

Current Trends in NSW

While comprehensive statistics are elusive, industry insiders suggest that interest in tiny houses has not waned entirely. Events such as the Tiny Homes Expo, held in Sydney earlier this year, continue to draw crowds eager to explore innovative designs and learn about the movement. Local builders, like Hauslein Tiny House Co., report steady inquiries, indicating that the idea of tiny living remains attractive, even if actual adoption has slowed.

However, logistical issues abound. Tiny house owners in NSW often face a patchwork of council regulations that treat their homes as caravans or temporary dwellings, limiting their use as permanent residences. This ambiguity forces many to operate in legal gray areas, such as situating homes on family-owned land without clear compliance.

Barriers to Growth

The story of tiny houses in New South Wales is, at its heart, a tale of ambition meeting resistance. It isn’t that the dream has faded—people still long for the simplicity, the sustainability, the freedom that tiny living promises. The obstacles, however, are formidable, rooted in the intricate machinery of laws, logistics, and land.

· The Knot of Regulation: In New South Wales, every council seems to tell a different story about what a tiny house is—or isn’t. One council might call it a secondary dwelling, something modest and permissible. Another might see it as a caravan, bound by rules meant for transience. For hopeful owners, the lack of uniformity turns planning into a puzzle, with pieces that never quite fit. Permits, when they’re required, can be costly and slow, testing the resolve of even the most dedicated.

· Infrastructure: The Hidden Hurdle: A tiny house is small by design, but it still requires a connection to the larger world. Water, electricity, sewage—these are not luxuries but necessities, and in rural areas, they’re often hard to come by. The appeal of an off-grid life fades quickly when the practicalities of modern living demand solutions that are neither simple nor inexpensive.

· Land: The Ground Beneath the Dream: Land is the foundation of any home, and in New South Wales, it’s a scarce and expensive resource. For those priced out of the urban sprawl, the search for affordable land feels like chasing a mirage. Some turn to private leasing, negotiating their way onto rural properties with the hope of staying under the radar. But these arrangements are delicate, subject to the whims of landowners and the ever-present spectre of council enforcement.

Where Do Tiny Houses Go?

For those without family land to fall back on, the question of where to place a tiny house looms large. The options, while varied, each come with their own compromises.

Private leasing seemed, at first glance, like a graceful solution—a partnership formed on mutual need. A small parcel of land, tucked behind a family farm or along the fringes of a sprawling rural property, might become the home that a tiny house owner had been searching for. There was a romance to the idea: the autonomy of owning your little sanctuary, the flexibility of negotiating terms that suited both parties, and the affordability compared to the prohibitive costs of traditional housing. Yet, as with all romances, reality complicated things. Council approvals loomed like unsolvable riddles, each municipality spinning its own web of rules. For every lease that flourished, another floundered, undone by misunderstandings or regulations too labyrinthine to navigate. And even for those who managed to piece it together, there was always the quiet threat of instability, a fragility that could never fully be ignored.

For those unwilling to take such risks, caravan parks offered their gates. Here, at least, the boundaries were clear, the arrangement spelled out in well-worn contracts. The promise of a place to park your tiny house, to connect to water and power, came with a caveat: it would never feel like home. Caravan parks, by their nature, invited transience. Spaces were shared, walls were thin, and the sense of privacy that tiny house living promised was inevitably diluted. Even when the arrangement worked, it was an exercise in compromise—a far cry from the permanence that so many tiny house owners longed for.

But then there were the communities, bright with possibility. Tiny houses gathered in clusters, forming villages that offered more than shared space—they offered shared life. Gardens tended together, communal kitchens humming with activity, neighbors bound not just by proximity but by choice. Here was the vision: not just a solution to housing but a reimagining of it, a chance to build something rooted in belonging. Yet, even these hopeful enclaves found themselves shadowed by bureaucracy. Regulation slowed their formation, marking them as outliers rather than pioneers. And so, while the dream of tiny house communities persisted, it hovered just beyond reach, waiting for a moment when the laws of the land might finally catch up with the ambition of its people

Comparisons with Other States

The story of tiny houses in New South Wales unfolds against a backdrop of untapped potential, especially when compared to the strides made in Victoria and Queensland. In these states, innovation and reform have breathed life into the tiny house movement, offering a glimpse of what could be possible with imagination and commitment.

- Victoria: A Model of Collaboration

Victoria has become a beacon of possibility, with the state government actively exploring the role tiny houses can play in addressing housing shortages. Pilot programs have emerged, designed to unite councils, builders, and community advocates in a shared effort to foster tiny living. These initiatives do more than provide shelter; they cultivate trust, creativity, and a sense of purpose. The result is a climate of welcome, where tiny houses are seen not as curiosities but as meaningful contributions to a larger solution.

- Queensland: A Blueprint for Reform

Queensland, too, has embraced the promise of tiny houses with open arms. The Southern Downs Regional Council recently rewrote its residential dwelling regulations, carving out space for tiny homes as a response to the affordability crisis. These reforms do more than change laws—they change lives, offering a clear pathway for those seeking a simpler, more sustainable way to live. Queensland’s approach serves as both inspiration and challenge to New South Wales, a reminder of what can be achieved with vision and effort.

The Role of Tiny Houses in Addressing the Housing Crisis

New South Wales finds itself at a crossroads. The housing crisis grows deeper, with affordability and availability slipping further out of reach for many. Tiny houses, while not a single answer, hold the potential to be part of a broader solution. Their appeal lies in their accessibility: a low-cost entry point for first-time buyers, a graceful option for those looking to downsize, a practical response to the urgent need for housing.

But the promise of tiny houses extends beyond individuals. Advocates see them as a way to ease pressure on social housing systems and provide transitional housing for vulnerable populations. Their small footprints align with the principles of sustainable urban planning, offering a chance to rethink not just how we live, but how we build communities.

And yet, this potential remains locked away, stymied by outdated regulations and a lack of cohesive policy. Without significant change, tiny houses will remain a dream deferred, a solution in waiting. In the successes of Victoria and Queensland, New South Wales can find both a mirror and a map—a reflection of its current struggles and a guide to what might be possible.

A Path Forward for Tiny Houses in NSW

For the promise of tiny houses to take root in New South Wales, the state must adopt a thoughtful, layered approach. It is not enough to admire the idea of tiny living; NSW must create the conditions for it to thrive.

- Regulatory Reforms: Clearing the Path

The first step is clarity. Uniform statewide guidelines for tiny houses could sweep away the confusion that currently defines the movement. By recognizing tiny homes as permanent residences—structures meant for living, not lingering—NSW can offer a sense of stability to prospective owners. Streamlined approval processes would ensure that enthusiasm for tiny living isn’t crushed under the weight of bureaucracy.

- Zoning Adjustments: Broadening Horizons

The idea of a tiny house tucked into a suburban backyard or perched on an urban lot shouldn’t feel revolutionary, but in NSW, it does. Expanding the zones where tiny houses are allowed would be transformative, increasing their viability for people who want to live simply without leaving behind the communities they call home.

Infrastructure Investment: Building Connections

Even the smallest homes need connection—to water, electricity, and sewage systems. The state can support modular, adaptable utility solutions that make tiny houses practical, particularly in rural areas where infrastructure is sparse. An investment in connection is an investment in possibility.

- Education and Advocacy: Shaping Perceptions

For tiny houses to flourish, they must first be understood. Public campaigns can shift perceptions, highlighting not just the practicality of tiny living but its beauty—the way it fosters sustainability, reduces consumerism, and creates space for community. Advocacy can turn the dream of tiny living into a shared vision, embraced by councils, developers, and citizens alike.

Conclusion

The tiny house movement in New South Wales is not a trend; it’s a promise waiting to be fulfilled. Tiny houses glimmer with the promise of something different, a modest yet meaningful answer to the housing crisis in New South Wales. They stand as symbols of ingenuity, their small footprints offering the potential to sidestep the pitfalls of traditional housing. But no amount of clever design can fully escape the weight of the larger system. The same entrenched problems that stifle conventional development—zoning restrictions, infrastructure demands, bureaucratic inertia—press down just as heavily on these diminutive homes. What begins as a vision of simplicity inevitably collides with a world that seems determined to make even the smallest solutions complex. Yet, the potential remains, quietly resilient, waiting for the moment when the barriers lift and their promise can take root.

What to learn more: My sources are your sources (except for the confidential ones):

- Hauslein Tiny House Co. (hauslein.com.au)

- "Rising Costs in the Building Industry" (tinynomad.com.au)

- "Tiny Home Friendly States" (casatiny.com.au)

- "Southern Downs Council Reforms" (couriermail.com.au)