René Magritte self-identified as the “painter of ideas,” but this exhibition, a sumptuous feast for the eyes and mind at the Art Gallery of NSW, reveals him to be something even greater: a conjurer of the uncanny. Spanning his career, the show pulls Magritte from the realm of the familiar and situates him firmly where he belongs—on the knife-edge between the ordinary and the extraordinary, where he explored the tenuous relationship between perception and reality.

A Career of Deceptive Simplicity

Born in 1898 in Belgium, Magritte’s trajectory as an artist was anything but linear. He began his career steeped in the then-raging fervor of Surrealism, though he always remained a somewhat aloof participant. While many of his contemporaries leaned into chaos and abstraction, Magritte took an opposite route. He made the ordinary strange, weaponising clarity to destabilise meaning.

His early works, like The Lovers (1928), are striking examples of this approach. In the painting, a man and a woman kiss through shrouded faces, their passion interrupted by an impenetrable barrier. Here, Magritte distills the existential alienation of the interwar years, a time when Europe, reeling from the trauma of World War I, grappled with broken connections and elusive truths.

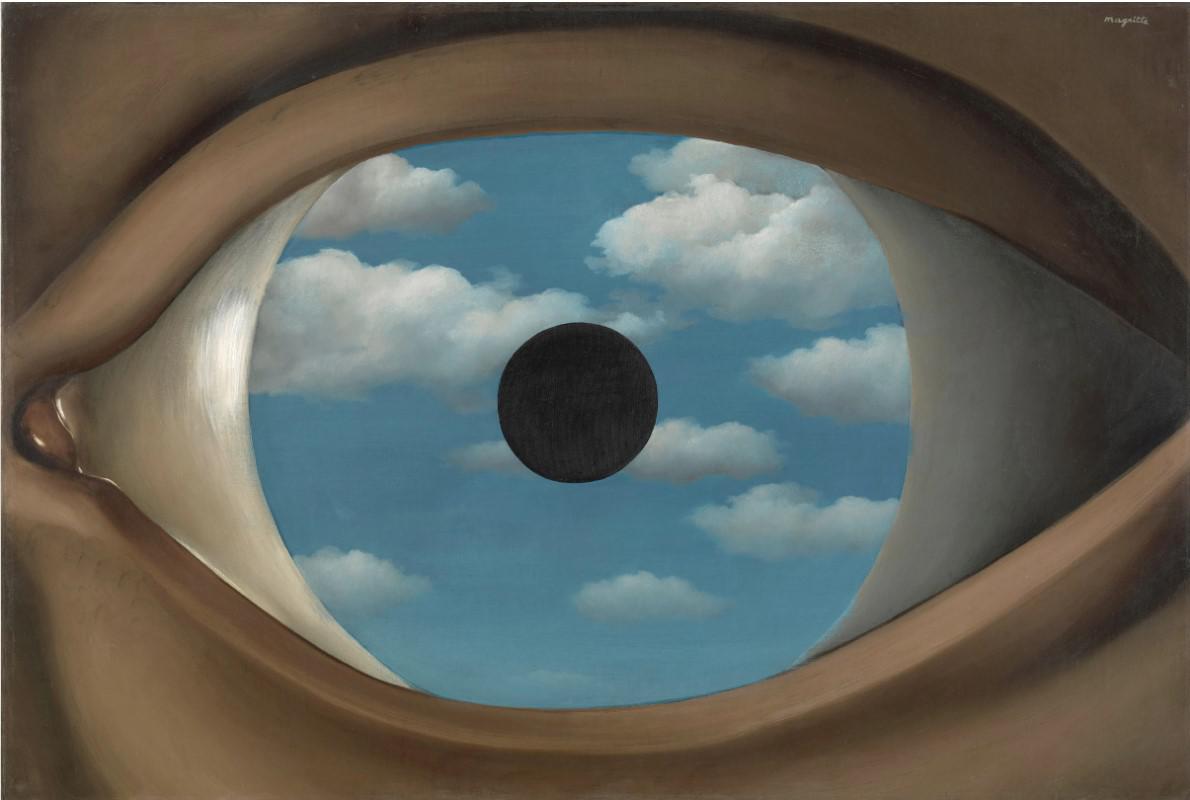

In The False Mirror (1929), Magritte presents an eye that stares at the viewer, its pupil replaced with a serene sky. The image, at once intimate and disconcerting, captures the surrealist credo: the collision of the inner and outer worlds. Painted in a period of economic collapse and rising fascism, the work feels prescient, as if Magritte were reflecting a world where nothing could be taken at face value.

By the 1930s, his work evolved further, as seen in The Human Condition (1933). The painting-within-a-painting motif, so central to Magritte's oeuvre, turns representation into a game of deception. What is real? What is illusion? These questions, which preoccupied a generation grappling with the collapse of old certainties, are made tactile here.

Magritte's work during and after World War II took on a darker, more introspective tone. In The Liberator (1947), he paints an enigmatic figure with a hollowed-out torso filled with an array of objects—a bird, a sky, a tree. It’s as if Magritte sought to depict the resilience of the human spirit while acknowledging the gaping wounds left by war.

His postwar works, like The Kiss (1951) and Golconda (1953), deepen his explorations of repetition and absurdity. Golconda, with its bowler-hatted men raining down against a flat cityscape, could easily be read as a commentary on the conformity of the postwar bourgeoisie. Yet it retains a playful ambiguity that defies simplistic interpretation.

Rene Magritte, Dominion of light. (One of 27 rendtions created by the artist. This version is from The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The Master of Light and Space

Perhaps the most enigmatic works in the exhibition are The Dominion of Light (1954) and The Listening Room (1952). The former depicts a serene daytime sky above a nocturnal street scene, defying natural laws and drawing attention to the boundaries of perception.

Magritte’s The Dominion of Light (1954) is an elegant paradox—a painting that makes you pause, question, and ultimately accept the impossible. At first glance, it’s a serene suburban scene: a street lamp quietly illuminates a house and its shadowed surroundings. The sky above, however, is a radiant blue, dotted with soft, sunlit clouds. Night and day coexist here, seamlessly and inexplicably.

Ever the conjurer, Magritte uses his signature precision to lull us into a false sense of security. The brushwork is steady, the palette restrained, the composition orderly. But the disjunction between the upper and lower halves of the canvas unmoors us. The impossible becomes the inevitable, as Magritte subtly dismantles the laws of nature we take for granted.

Painted in the mid-20th century, The Dominion of Light reflects its time: an age of dualities—optimism shadowed by Cold War dread, technological leaps tempered by existential unease. Yet, like all great art, it transcends its moment. The painting’s quiet brilliance lies in its ambiguity. Is this a meditation on perception, a dreamscape, or a philosophical riddle? Magritte offers no answers, and that’s precisely the point.

In The Dominion of Light, Magritte reminds us that art need not explain; it need only make us see differently. And in that, he achieves dominion not just over light, but over our imaginations.

In contrast, Magritte’s The Listening Room (1952) is a study in quiet absurdity, the kind that whispers rather than shouts.

It is quintessential Magritte: familiar objects rendered absurdly monumental, forcing the viewer to confront their own cognitive dissonance.

At its heart is a single, audacious gesture: a massive green apple, its surface waxy and luminous, occupying almost the entire volume of a modestly scaled room. The apple’s size is incongruous, even oppressive, its presence rendering the room’s walls claustrophobic. It is both monumental and banal, a fruit transformed into a philosophical conundrum.

Magritte’s genius here lies in his ability to destabilise our sense of proportion and purpose. The room—ordinary, nondescript—anchors us in a familiar reality. Yet the apple’s scale and placement warp that reality, nudging us into the realm of the surreal. The painting feels like a riddle: What is the apple listening to? Us? The room itself? Or is it merely existing, indifferent to the questions it provokes?

Created in the aftermath of World War II, The Listening Room may carry the weight of its era. The tension between confinement and immensity could reflect a postwar world grappling with the enormity of human experience compressed into fragile spaces of recovery and reflection. Yet Magritte resists pinning down meaning. His apple is neither allegory nor symbol—it simply is.

Magritte once said that his work sought to make “everyday objects shriek aloud.” In The Listening Room, he succeeds not with a scream but with a hushed, resonant echo. The apple fills the room, but its true enormity lies in how it expands the mind.

Both works exemplify Magritte’s ability to distill vast philosophical concepts into images of disarming simplicity. They speak to the anxieties of their era—the Cold War, the threat of nuclear annihilation—but also to timeless questions about humanity’s place in an unknowable universe.

Magritte's Enduring Legacy

The Art Gallery of NSW’s curatorial approach is restrained, allowing Magritte’s enigmatic canvases to take center stage. His works remain as fresh and perplexing as they were decades ago, speaking to a world still grappling with uncertainty. Magritte’s genius lies in his refusal to resolve these uncertainties. Instead, he invites us to linger in them, to relish the tension between what we see and what we think we know.

This exhibition is not just a retrospective but a reminder of Magritte’s relevance. In an age of artificial intelligence and augmented realities, where the boundaries between real and virtual grow ever more porous, his explorations of perception and deception feel more urgent than ever.

René Magritte: The Painter of Ideas runs at the Art Gallery of NSW through February 9, 2025. Don’t miss it.